Homily For 3rd Sunday Advent Year C (Gaudete)

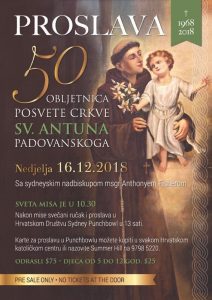

HOMILY FOR MASS FOR 3RD SUNDAY ADVENT YEAR C (GAUDETE) + 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF DEDICATION OF ST. ANTHONY OF PADUA CATHOLIC CROATIAN CENTRE

St. Anthony of Padua Chapel, Summer Hill

When we think of nineteenth century comic operetta we naturally think of evan zâytz Ivan Zajc; but one of the best-loved comic operas is not his but Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado. Set in ‘far away Japan’, it parodies English customs through a drama surrounding the Emperor of Japan and his son Nanki-Poo, who has run away to marry a girl called Yum-Yum. In the play’s comic denouement, Nanki-Poo is condemned to death, but is spared by Ko-Ko, the Lord High Executioner. When his supposed-to-be-dead son turns up again, the Mikado angrily demands an explanation. “It’s like this,” the official explains, “when your Majesty says, ‘Let a thing be done’, it’s as good as done – practically, it is done – because your Majesty’s will is law. Your Majesty says ‘Kill a gentleman’, and the gentleman is to be killed. Consequently, that gentleman is as good as dead – practically he is dead.” So though Naki-Poo was not actually dead he was legally and ‘practically’ so! The Mikado answers that this is “most satisfactory”.

This strange logic of being, for instance, dead when you are alive recurs throughout the play. Though comical, it has its serious side and resonates with those inversions so common in the Christian Gospel: that those who’ve worked night and day for God will get the same reward as those who turn up at the end; that the poor and powerless and persecuted are to be counted the most blessed; that the first will be last and the last first; that we must give up our lives in order to gain them; that we should welcome strangers and love enemies… The logic of the Kingdom of heaven often seems more Gilbert and Sullivan than Shakespeare.

Indeed it seems that God loves upsetting our ordinary human thinking and doing. He replaces our mundane notion of ‘just desserts’ with a heavenly notion of ‘just mercy’. When we think we’ve got Him summed up and tamed, He does or reveals something unexpected. Every time we think we’ve got the Gospel down pat and ticked off, God subverts our plans. It’s this comic inversion that explains the rose colour of Laudate Sunday.

Advent is a season of such logical inversions. We long for Christ’s coming at Christmas, while knowing He has already come; we know He’s here amongst us, yet we look forward to His coming again. We know He ushered in God’s kingdom, yet still we pray ‘Thy kingdom come’. Advent is at once remembrance and anticipation, a twilight between now and not yet. Ours is, in fact, a ‘now and not yet’ faith. What we experience now, the Catechism says, is but a foretaste of things to come (CCC 163). ‘When we contemplate the blessings of faith we enjoy even now,’ St. Basil wrote, ‘it is as if we already possessed the wonderful things which our faith assures us we shall one day enjoy.’[1] ‘Shout for joy’ and ‘exult with all our hearts’, Zephaniah sings this morning, as if God’s coming kingdom has already come (Zep 3:14-18). The purple gives way to rose.

How is it possible for someone to be both dead and alive? How can we hope for what we already have or be grateful for what we have not yet received? What is this kingdom we call ‘heaven’ that is here already and still a long way away? Well, heaven is in a sense a place – because there are bodily beings there – and so we profess that Christ is ‘seated at the right hand of the Father’ and that the just are with Him ‘in’ heaven. Yet in another sense it is far more than any place, any holiday destination – even on the spectacular Dalmatian coast – because those who have experienced the Resurrection, like Christ, will be unconfined by space or time. In heaven we experience total communion with God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, with the angels and saints, with all we’ve loved and lost but who’ve been saved in Christ. Here on earth we have to choose to be present at this destination or that, to keep company with this person or that, to make conversation with this one or that. Each choice costs us the alternatives; each focus distracts us from attending to another. But the freedom of heaven allows us to have all that is good and true and beautiful, and to focus totally on each instance. Heaven allows us to have ‘beatific vision’ as the Dominican St Thomas called it, or ‘beatific union’ as his Franciscan mate St Bonaventure named it – purifying us of unnecessary limitations, infusing our minds with insight, and filling our hearts with ‘the ever-flowing well-spring of happiness, peace, and mutual communion’ (CCC 1045).

Some think of heaven as an amorphous state, a myth we tell ourselves because we are afraid of mortality, a fairy-tale of fluffy clouds on which angels play harps around a celestial throne. Yet, for the Christian, it’s more real than anything on earth we can see and touch, more tangible than any physical reality, and more eternal. Being with God is precisely what we are made for; every fibre of our being cries out for it; we are less while ever we are not fully in communion with our Creator and will be more when we finally are. Like the logic of The Mikado, the logic of Advent is that we already glimpse heaven, even if we’re not yet there: in the Eucharist, when the heavenly liturgy is brought to earth and the God-man really present on our tongues; in the Word of God and teachings of the Church, by which we plumb mysteries beyond the mind of man; in that faith and forgiveness preached by the Baptist this morning and received by the Christian soul (Lk 3:10-18); in our experiences of life and love, of family and friendship, creation and redemption… All these are divine graces, communicated even now, yet pointing to more to come.

If the heavenly kingdom is so close, why does John keep harping on about repentance? Is he just a party-pooper, with all this ominous talk of winnowing, threshing and burning? (Lk 3:10-18) Well, as Jesus’ many stories of heaven as a party make clear: you can’t force people to party, you can’t require them to turn up, let alone get into the spirit of the occasion (Lk 14:7-14; Lk 14:15-24; Mt 22:1-14). They have to want that, choose that, for themselves. Heaven isn’t the only afterlife possibility, not the only foretaste on our tongues in this life. We can choose the opposite if we like. God invites, exhorts, cajoles, time and again. But He refuses to turn us into puppets, or robots, or slaves; He won’t do violence to us, even to get us to heaven. Instead of saying “God loves us too much to let anyone go to hell” we should say that “God loves us too much to force anyone to join Him in heaven – but He’ll do everything short of forcing us to get us there.”

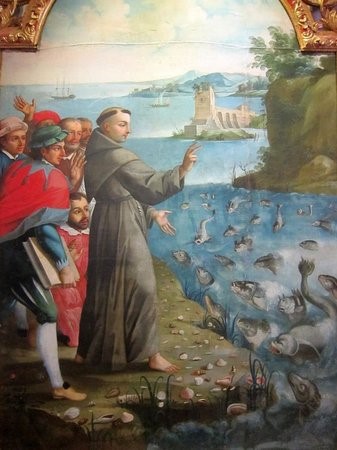

The patron of the Croatian Catholic Centre, St. Anthony, belonged to that other, non-Dominican football team, the Franciscans, but he is dear to me as my name-saint. He so wonderfully embodied the divine comedy that on one occasion, when the people of a coastal town like Sydney wouldn’t listen to him, he preached instead to the fish, who leapt out of the sea to hear him!

I’m not sure how much the friars here in Summer Hill preach to the sharks, but this place is known for its sacraments and celebrations, its thriving youth group with courses, retreats and other activities, its devotions, church picnics, prayers for the dead, and the rest. When my predecessor Cardinal Gilroy dedicated this chapel fifty years ago, he praised the “heroic fidelity to God and their homeland” for which Croatians were famed – a faithfulness that had survived endless invasions by great powers and ideologies over the centuries, because it was rooted in that intellectual and affective union with God of which Christian life is a foretaste.

The Mikado-esque reasoning of our Advent God is this: ‘If you believe and keep my commandments, then you’re as good as in heaven – practically, you are in heaven’. But it’s not the only option. So when Paul tells us not to worry, he also tells us to pray, to keep build our friendship with God and each other. The Croatian Chaplaincy is here for that: may it long demonstrate the Gaudete spirit of joyful Christian gratitude and anticipation. A very happy fiftieth birthday. Ad multos annos! Thanks be to God for you!

INTRODUCTION TO MASS FOR 3RD SUNDAY ADVENT YEAR C (GAUDETE) + 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF DEDICATION OF ST. ANTHONY OF PADUA CATHOLIC CROATIAN CENTRE

St. Anthony of Padua Chapel, Summer Hill

Dragy Krvati [Dragi Hrvati = Dear Croatians]

Welcome to our Solemn Mass celebrating the golden anniversary of the St Anthony’s Croatian Catholic Centre on this, the Third Sunday of Advent, known as ‘Gaudete’ or Rejoicing Sunday. The day takes its name from the Introit, Opening Prayer and readings which all exhort us to Rejoice as if Christmas were already come. And so while there are still nine shopping days to Christmas, the Church is already dressing her priests up in Christmas wrapping.

Concelebrating with me today is fra Ivan Matić OFM, Vicar General of the Franciscan Province of Croatia; fra Zvonimir Krizanović OFM; fra Vladimir Novak OFM; fra Mate Mučkalović OFM; fra Petar Horvat OFM; and fra Josip Kešina OFM – and others. From civil society I acknowledge: Her Excellency, Ambassador Pavelich of the Republic of Croatia; Consul-General Glasnović of Croatia; Senator Zed Seselja, Assistant Minister for Treasury and Finance; Hon. Anthony Albanese MP, Member for Grayndler and Shadow Minister for Infrastructure and many other things!

To all members and friends of the Croatian Catholic Centre and chaplaincy, a very warm welcome!

[1] St. Basil, De Spiritu Sancto, 15, 36