Homily for the Red Mass

St. Mary’s Cathedral, Sydney, 30 January 2023

In a recent Quarterly Essay entitled “Uncivil Wars: How contempt is corroding democracy”,[1] Waleed Aly and Scott Stephens addressed the contemporary phenomenon that every demographic feels victimised, and every issue draws sharp lines between us. Opposing sides consider themselves shamed and cancelled and regard the others as bullies and “deplorables”. Outrage and contempt are the emotions of the age. This undermines our ability to dialogue and govern—and, I would add, render justice. Indeed, it threatens our ability to relate even to our nearest and dearest: SBS recently published a comment piece on “How to survive your conservative relatives this Christmas.”

The authors argue that this omnipresent contempt corrupts our politics, journalism, common life. For democracy, including I dare say our justice system, to flourish, citizens must relate less like rivals than like spouses, bound together by reciprocal devotion, and hopefully discovering and practising the ethical conditions for their union to persist. In particular, they conclude, we must learn again habits of patience, reciprocity and free exchange.

Jesus famously echoed the Old Testament teaching (Lev 19:1-2,11-18) that we must love our neighbours as ourselves.[2] He thought that on this commandment, and the one to love God before all else, hangs the whole of the Law (Mt 22:40)—including civil law. Sometimes people take this to mean loving others as much or in the way they love themselves: but that’s a very imperfect measure, given how disordered self-love can be, and how often people have low self-esteem or even self-hatred. So let’s examine the Levitical teaching more closely.

First, who is this teaching for? The Lord tells Moses to “Speak to the whole community of the children of Israel”. In other words, this teaching is for everyone. We are not divided into castes of the righteous elite and the beasts incapable of fulfilling the law. We are moral equals by virtue of our being created in the image of God (Gen 1:28). All human beings are called to fulfil the commandments that regulate our neighbourliness.

Secondly, what is this neighbourliness? Moses and Jesus say it is at its core an imitation of the way God loves: be holy as God is holy; be perfect as God is perfect. Neither expects we will ever achieve this. But conforming our hearts and minds, actions and relationships to God’s will found the habits so sorely needed for a healthy common life.

Thirdly, Moses gives some examples of this godlike regard: respecting each other’s property and other entitlements, care for the weak, honesty in dealings; no perjury, slander or partiality in courts, no hatreds or vengeance nursed in hearts: a community founded not on contempt but on practical neighbourly love.

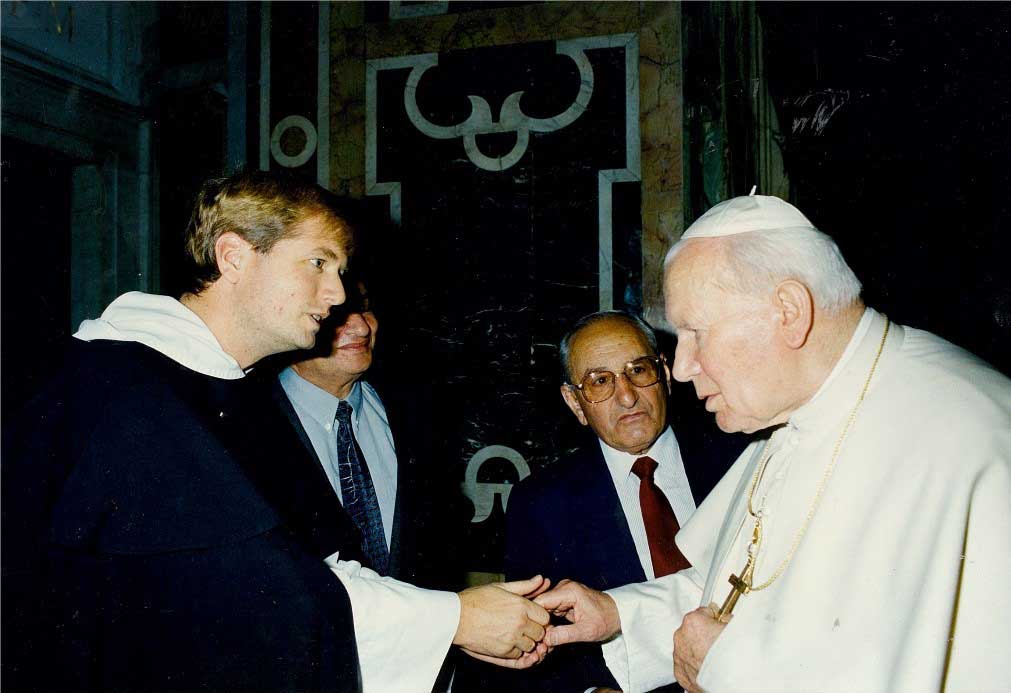

When newly pope, St John Paul II proposed to lawyers that the purpose of law is not just regulating a society so it is predictable and orderly, or so rights are respected and responsibilities fulfilled, or so people are shielded from arbitrary power. No, law must also cultivate a certain kind of character. “Law plays a role that is in the highest degree educative, both of individuals and of society,” he said. For people to come into being and mature “in an integral way” they need such “an ordered and fruitful environ-ment”.[3] Few would deny the educative power of law. But John Paul’s thought is that learning the rules and to do as we’re told is not enough. We must understand what underpins common life: reverence for the divine order and the human person.

That’s not just for citizens, but also for lawmakers, judges and lawyers too. These ‘priests of justice’, as Ulpian called them, must do more than make and enforce rules: they must go beyond mechanical justice to equity and even love. Asking legal professionals to be great lovers might seem too much, especially when we consider some of the characters they must deal with. Yet if love without justice can be very partial, justice without charity can be too harsh, in the ways our Scriptures warn against, so we demonise others as ‘enemies’, cancelling and trolling them, feeding an endless cycle of vengeance.

Years ago, we probably all read Terence Rattigan’s play The Winslow Boy, or saw it on stage or film. It’s the story of a young Navy cadet accused of stealing a postal order, and his father’s fight through the courts to prove his innocence with the help of London’s top advocate, Sir Robert Morton. But Rattigan never takes us into court; instead, we see the effects of the proceedings on people outside. In the final scene, we hear that the great barrister wept in court at the vindication of his client’s innocence. When the family’s suffragette daughter, Catherine, asks him if he wept for justice, Sir Robert replies: “No, not justice—right. It is easy to do justice; very hard to do right.”

This captures something of what Moses, Jesus and John Paul meant when they spoke of a justice that seeks mercy, even love. Unless we find a way to reverence even those who are hardest to love, we cannot bring the impartiality necessary for right judgment and we cannot sustain the kind of character and common life that the law is there to instil and serve.

From my memories of my law school days, there wasn’t much talk of love of enemies, prayers for persecutors, or seeking heavenly perfection. Yet as Jesus reminds us today, God the perfect judge “causes the sun to rise on bad men as well as good, and his rain to fall on honest and dishonest men alike”—demonstrating an impartiality between persons that is hard to achieve and a partiality towards each person based upon love for every one of them as another self. This repudiation of contempt and determination to see the good and true and beautiful in the other is foundational for our civil life. It must be a guiding light for our priests of justice. God bless you in your important work.

[1] Waleed Aly & Scott Stephens, “Uncivil Wars: How contempt is corroding democracy,” Quarterly Essay 87 (2022) 1-71.

[2] Mt 19:19; 22:39; Mk 12:31; Lk 10:27; Rom 13:9-10; Gal 5:14; cf. Mt 5:43-48; 7:12; Lk 10:29-37; Jn 13:34; 1Cor 10:24; Phil 2:3; Eph 4:25-32; Heb 13:1-2.

[3] John Paul II, Address to the Tribunal of the Roman Rota, 17 February 1979. On the educative function of the law see also: Brian Burge-Hendrix, “The educative function of law,” in Law and Philosophy (OUP, 2007), pp. 243-255; Ian Ward, “The educative ambition of law and literature,” Legal Studies 13(3) (1993): 13-26; Christopher Eisgruber, “Is the Supreme Court an educative institution?”, New York University Law Review 67 (5) (1992): 961-1033.

Introduction to the Red Mass – St. Mary’s Cathedral, Sydney, 30 January 2023

Welcome to St Mary’s Cathedral Sydney for the annual Red Mass, marking the opening of the 2023 law term. The first recorded Red Mass was celebrated at Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral in 1245. In England the tradition dates to around 1310 during the reign of King Edward II and it became known as “the Red Mass” because of the scarlet robes worn by the royal judges. Sydney’s tradition is not quite so long, but this is our 92nd year since the first Red Mass was celebrated in this cathedral in 1931.

I acknowledge the concelebrating clergy, including Fr Peter Joseph, chaplain to the St Thomas More Society, and I thank the Society for assisting in organising this occasion.

Amongst our lawmakers I acknowledge: Hon. Mark Speakman SC MP, Attorney General of New South Wales, who in a sense he stands in the shoes of our patron Thomas More who was Chancellor of England; Hon. Michael Daley, Shadow Attorney General of NSW; Hon. Damien Tudehope MLC, Minister for Finance, and Minister for Employee Relations, Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council, and Vice President of the Executive Council; Hon. Dr Hugh McDermott MP, Chair of the ALP Law and Justice Committee; other ministers and members of parliament past and present; and all those associated with government.

Amongst our judiciary I salute: Hon. Justice Andrew Bell SC, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of NSW; Hon. Justice Julie Ward, President of the NSW Court of Appeal; Hon. Justice Derek Price AO, Chief Judge of the District Court of NSW; Hon. Brian Preston SC, Chief Judge of the Land and Environment Court; Hon. Judge Peter Johnstone, Chief Magistrate of the Local Court of NSW; Hon. Judge Gerard Phillips, President of the Personal Injury Commission of NSW; Commissioner Nichola Constant, Chief Commissioner of the Industrial Relations Commission of NSW; and judges, magistrates, and members of State and Federal courts, tribunals and commissions; and all those associated with them.

I also recognise Mr Michael Sexton SC, Solicitor General for New South Wales; Ms Cassandra Banks, President of the Law Society of NSW; along with barristers and solicitors.

From the legal academy I welcome: Ms Susan Carter, Director of the Law Extension Committee at the University of Sydney; Professor Michael Quinlan, Dean of the University of Notre Dame Law School; and other legal academics, along with law students. I gratefully acknowledge the members of the Choir of St John’s College in the University of Sydney, directed by Mr Richard Perrignon. At this Mass we pray for members and friends of the St Thomas More Society or of the legal profession who have died, including most recently Sir Gerard Brennan, 10th Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia; and Janet Coombs, the longest practising female barrister in NSW and our first ever lay canon lawyer. We also remember Sir Cyril Walsh, former Justice of the High Court of Australia, whose 50th anniversary of whose death occurs soon.

To anyone associated with the law, a very warm welcome.